How does InDesign calculate DPI?

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

I suppose from the image resolution and the print size.

If so, does it use an average printer dot size for the calculation or most printer dots are of the same size?

I am trying to get the DPI based on these 2 values in Photoshop, but it only shows PPI.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

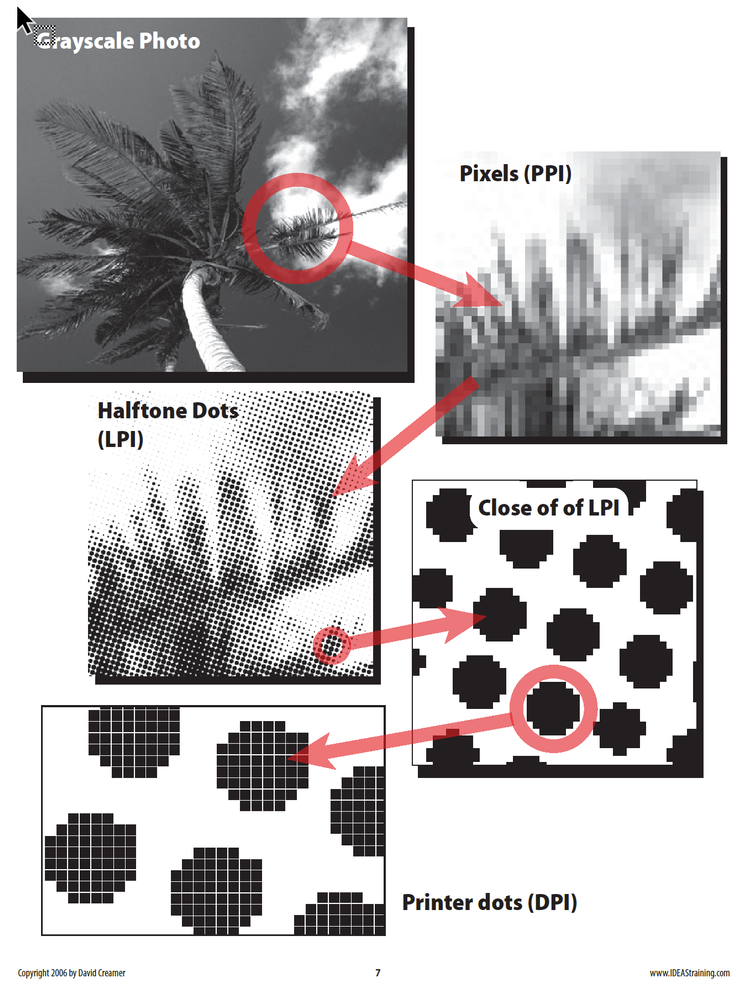

There is a differnce between image resolution (pixels per inch, which folks used to refer to as DPI incorrectly) and the number of printer dots per inch, which is better referred to in a converntional haltone as LPI (lines per inch).

What matters to you is the EFFECTIVE resoltion, in PPI, of any image placed in InDesign. This is calculated by dividing the scaled dimensions of the image (in inches) by the number of pixles in the image in each direction.

Resolution in Photoshop is a myth. It doesn't actually exist. What you see listed in the image size dialog is the theoretical resolution of the image if it is reproduced at the listed dimensions. If you change the resolution or dimensions in that dialog without resampling you will see they change together in inverse relationship and the actual number of image pixels remains constant.

Until they are output, images are only pixels and have not phyical dimensions or resolution.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

I again mildly disagree that DPI and LPI are the same thing, but we'll let that pass. PPI is correct in all situations except ink on paper.

If there is a single technical issue more widely misunderstood than any other in this field, it's what "image resolution" means and the perpetual mis-reference to "300 dpi (or ppi)" images and such. Not grasping the relationship between image dimensions and the relativity of display or print resolution is... arrrrgh.

But then, the tendency to refer to "2 meg images" and such, as if that means anything at all... double arrrrgh.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

"I again mildly disagree that DPI and LPI are the same thing"

Indeed; I would say I strongly disagree! 😉

e.g. An imagetter that has a resolution of 2400 DPI printing a halftone line screen of 150 LPI is definitely not the same measurement comparison.

Anyway.. historically, way before laser printers, DPI was used to describe the resolution of optical drum scanners and typesetters "back in the day", so the reference kind of came down the line until the industry redefined image resolution as PPI, which is more accurate a descripion, so I get where the confusion comes in.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

mea culpa. I misspoke, so to speak.

The important thing here is that what matters in InDesign is effective resolution, and what that should be is entirely dependent on the output method and the intended viewing distance (no point in making billboards at 300 ppi when they're viewed from thousands of feet).

In classes I used to teach I tried to illustrate the relationship between pixels and resolution by using a balloon with a checkerboard drawn on it. Each square represented a single pixel. As you inflate the balloon the size of the squares expands and the number of square per inch (resolution) goes down, but you don't alter the number of pixels.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

In classes I used to teach I tried to illustrate the relationship between pixels and resolution by using a balloon with a checkerboard drawn on it. Each square represented a single pixel. As you inflate the balloon the size of the squares expands and the number of square per inch (resolution) goes down, but you don't alter the number of pixels.

By @Peter Spier

That’s a nice demonstration.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Is this something like "printer dot ratio", similar to device pixel ratio?

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Not really. It's so simple it can be hard to get across, since it's so embedded in casual understanding that an image is "300 dpi" or whatever. It's like saying a car is 180 MPH... it sort of sounds right but is really meaningless.

An image file has only three characteristics: its width in pixels, its height in pixels, and then its color encoding. It has no inches, picas, millimeters or other measurements. All such measurements are completely relative to how an app maps the image's pixel dimensions to a final screen or print size. An image doesn't have ANY PPI until it is assigned a display or print size.

That you can encode a default PPI in an image file, in Photoshop for example, is probably why it's misunderstood. If you create a file and assign it 300 PPI, it must be "a 300 PPI file"... right? No. It's a 1200 pixel by 1200 pixel file (or whatever), and some apps will read that default PPI and automatically place and scale it at 4 inches by 4 inches... but other than that brief moment of convenience (which isn't convenient, if you wanted the image placed at 2 x 2 inches)... the embedded PPI is meaningless. You could assign it 10 PPI in Photoshop, or 1238 PPI, and it would be exactly the same image file.

In InDesign, the only portion of this that matters is when you place and scale an image, and then look at the Effective PPI... if it's a 1000 x 1000 pixel image and you've placed it at 8 x 8 inches, the Effective PPI will be 125 PPI, probably too low for quality printing but probably okay for screen display.

All meaningful PPI are this "effective" or "resulting" value... nothing inherent in the image file itself. There is no such thing as "a 300 PPI image" unless you are working in a rigidly defined environment where all archive images will be printed at a specific size and the PPI is thus fixed by that value. In other words, almost never.

The ratio of DPI (what a printer is capable of and the number of ink dots per inch it can create) to LPI (what the final visual resolution of the print is, linescreen or stochastic pattern) is closer to what "printer dot ratio" means.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Is this something like "printer dot ratio", similar to device pixel ratio?

By @Chris P. Bacon

Device pixel ratio is a way of getting to a device-independent unit of measure for screens (the device-independent pixel or DIP), which could function for screens the same way inches/cm do for print. One inch is one inch on any printer (that’s device-independence), even where printers have different hardware dots per inch. On screens, one DIP is about the same size on screens of different dpi, but as in print, can be built from multiple device hardware pixels.

So in both cases, you have device-specific hardware pixels (screen or printer DPI) that provide more or less detail per device-independent unit of measure (DIP or inch/cm), which stays constant across devices.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

DPI is the print device resolution, which is set by the printer driver not InDesign.

As Peter suggests most print devices convert a continuous tone image into either a halftone screen, which has a resolution referred to as Lines Per Inch (LPI), or a stochastic screen.

The halftone screen dots are drawn with the smaller printer dots, and the illusion of tonality is created by modulating the size of the halftone dot. A platemaker outputting at 2400 dpi can accurately draw a 150 line halftone screen, my 1200 DPI laser printer can draw a 90 LPI halftone screen.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halftone

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stochastic_screening

InDesign can read and scale image resolution, which is referred to as Pixels Per Inch (PPI). The image resolution of a placed image at 100% is listed as Actual Resolution in Link Info panel, and the scaled image resolution is listed as Effective Resolution. If you scale an image with an Actual Resolution of 300ppi to 50%, the pixels are half the original size so its Effective Resolution is 600ppi.

On a PDF Export you can downsample and lower the Effective Resolution via the Compression tab (you can’t upsample on a PDF export)

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

I can agree with that: DPI is the physical measurement of what a digital printer can apply, and LPI is the measurement of the result on the paper.

But both are largely irrelevant to ID and design work unless specific coordination with a printer (box or service) is needed. Image dimensions and PPI are all.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

I would agree with that as well. Late in the day here...

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Then, since my image workflow is Photoshop > Illustrator > InDesign, the only thing I have to do is to make sure that at the image dimension in Photoshop at least 300 is set as the image "Resolution", right? Before I export it to the other apps.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Not exactly. You need to have an EFFECTIVE resolution that matches your output size.

If the required output effective resolution is 300 ppi (the rule of thumb for offset print to be viewed at arms' length), then in photoshop your image must be 300 ppi when the image dimensions match the print size. PPI numbers in Photoshop are meaningless except in relation to an output dimension. The same pixels can have any resolution from less than 1 ppi to thousands of ppi depending on the output size.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

the only thing I have to do is to make sure that at the image dimension in Photoshop at least 300 is set as the image "Resolution", right? Before I export it to the other apps.

You would have to consider whether the image is being scaled anywhere in the workflow. If there’s any scaling applied to the image it would affect the effective output resolution—if the cumulative scaling to the image is 120% the final output resolution would drop to 250ppi.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Reminds me of one of those "scale of the universe" illustrations. 🙂

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

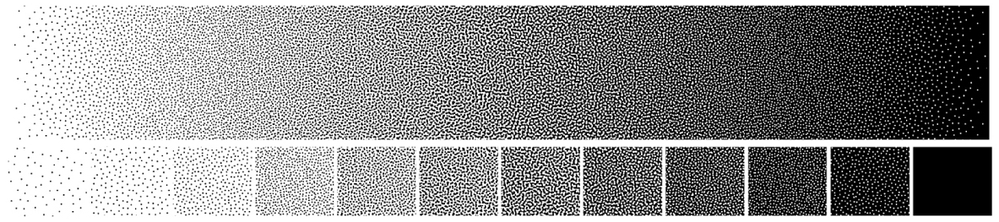

Also, highend offset and inkjet printing can use stochastic screening—I think of LPI as a measurement of AM halftone screens where the printed dots change size.

Stochastic frequency modulated screening creates the illusion of tonality by changing the spacing of small, same sized dots:

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

DPI / 16 = LPI (optimum)

PPI of the image file = minimum 1.5 * LPI and max 2.0 * LPI.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

DPI and LPI only really matters for lithographic printing.

The actual figure is 1.41^ x LPI

Different ouputs and substrates would use different LPIs

Newspapers - 80-120 LPI would yield 112.8 to 169.2 DPI

The 1.41 is the rotation of a square so it's measured tip to tip.

A square with 1x1 on all sides is always 1.41 from corner to corner.

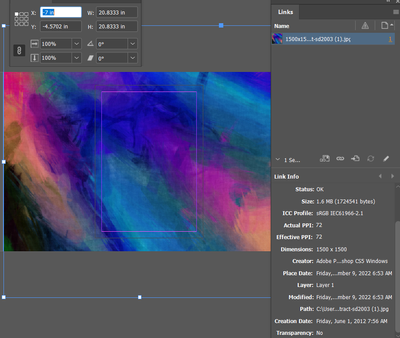

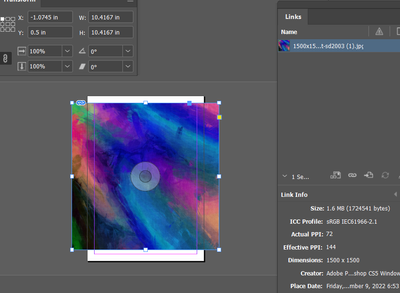

Anyway - how does InDesign Calculate it?

Same was as you can

If it's 1500 x 1500 @ 72ppi

You place that at 100% then it's 1500 x 1500 with 72 pixels per inch

Your size is 1500/72 = 20.83inches

If you place it at 50%

And it's half the size

And double the resolution

A 72PPI image placed at 24% will yield 300PPI

If you wanted to know what that size is before placing.

Original size is 1500 x 1500

so it's 1500/300

= 5 inches

That's it - basic division of the Pixels by the resolution.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

DPI and LPI only really matters for lithographic printing.

The actual figure is 1.41^ x LPI

Hi Eugene, I think the idea that there is a multiplier that works for all images assumes the halftone screen pattern is uniform, but that’s not the case with images that have areas of fine details at high contrast—higher resolutions would be decernible in those types of images.

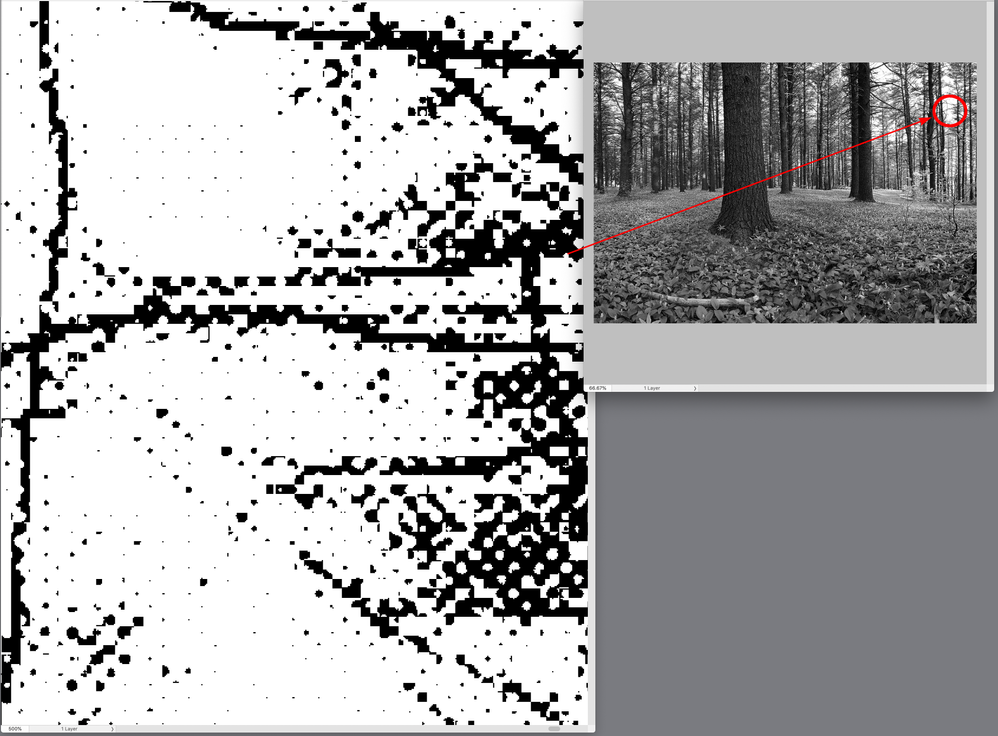

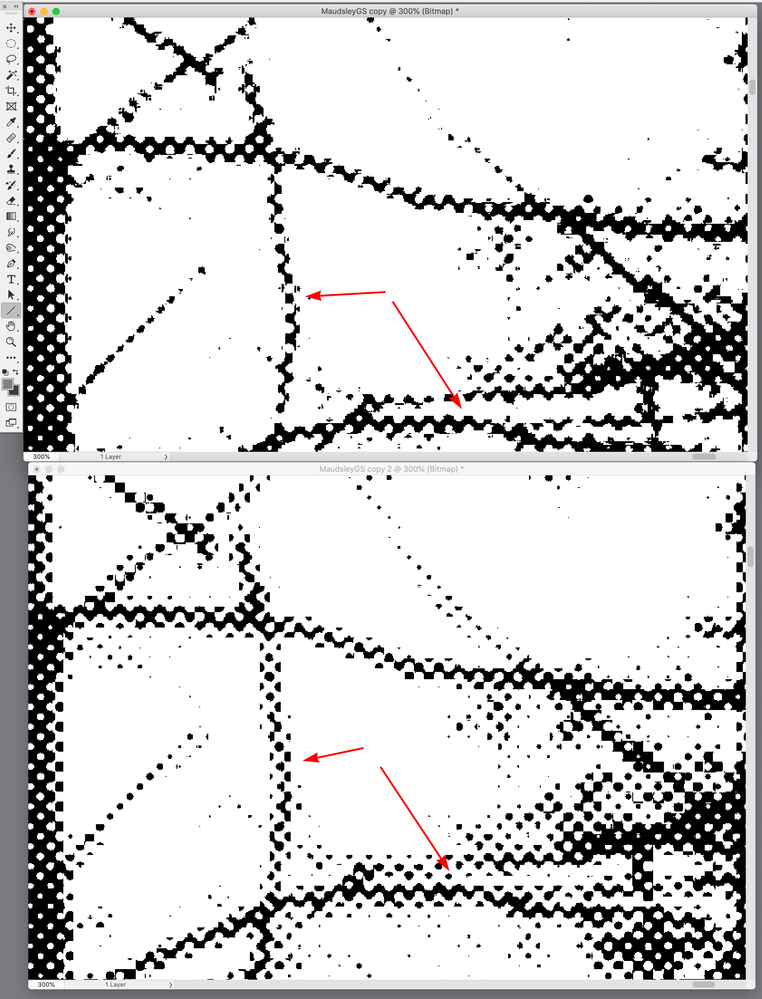

In this halftoned example the fine details in the tree branches approach line art and there’s no longer much of a screen pattern running interference:

Here are 150 LPI simulations at 2400 DPI—600ppi top and 210ppi bottom. I can see the structure of the halfone screen in the branches is different—in the 210 version they are fatter and softer:

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Of course - you are correct.

I didn't delve into every scenario available.

for black and white and grayscale images there's different rules.

I was speaking generally.

And of course, didn't go into digital/flexo/gravure/screen/litho etc. specicifically.

My goal was to dispel the 300 DPI myth for print as being erroneous as it relies on various things.

You could have a foggy scene and printed at 120DPI from a 150LPI would look just fine.

But a picture of a face with detail at 120DPI with a 150LPI would not look good.

My goal was to share an interesting fact that there is a calculation behind the 300 DPI.

Bascially stems from I believe an easier calculation, 150LPI x 2 = 300

But yes, different images, and different scenarios require care and attention.

Lineart could be 1200PPI or even 2400 PPI.

Thank you for taking the time to bring this up to.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

I suppose from the image resolution and the print size.

If so, does it use an average printer dot size for the calculation or most printer dots are of the same size?

I am trying to get the DPI based on these 2 values in Photoshop, but it only shows PPI.

By @Chris P. Bacon

Some definitions (some of which are already discussed):

- PPI. Pixels per inch, which you get by dividing the pixel dimensions by the physical dimensions. This is device-independent.

- Effective resolution. PPI resolution after final scaling on the layout is taken into account.

- DPI. Dots per inch, which really means device hardware dots per inch. This is not shown in Photoshop Image Size because device dots are not represented there. This is obviously device-specific, so it does not apply until the document reaches the printer.

- LPI. Lines per inch, used for processes involving halftone dots built from device pixels. LPI is not used as much as in the past because digital printing processes today (such as inkjet printers) tend to use other screening processes such as irrational/stochastic/FM screening.

Example: You need a 300 ppi print of an image. Just saying 300 ppi actually isn’t enough information, because per the definition above, to get to PPI you need to know both the pixel dimensions and final physical size (inches/cm) of the print. If you say the physical dimension needs to be 10 inches wide, adding that value resolves it: To achieve 10 inches wide at 300 ppi, the image must be 3000 pixels wide (10 inches times 300 ppi). Of course you can use Photoshop Image Size to work that out.

Suppose the printer is a commercial digital printer or platesetter with a hardware device resolution of 2400 dpi. That means you will print a 300 ppi image on a 2400 dpi printer. The image doesn’t have to be 2400 dpi, because those dots are used to build the screening pattern that renders image tones and colors. (Type and vector graphics do render at device dpi.)

If it was a halftone printing process, then you could have three numbers — which are all true for the same image: A 300 ppi image, printed on a 2400 dpi device, using a 150 lpi halftone screen (150 lpi halftone dots built using the smaller 2400 dpi device hardware dots).

But the ppi resolution of an image changes if you resize it on a print layout. If you halve the physical length on the layout (without cropping), the image ppi must double. So a 3000 px wide image prints at 300 ppi at 10 inches, and also at 150 ppi when 20 inches wide, and at 600 ppi when 5 inches wide. The ppi resolution after final scaling is the Effective PPI resolution. Photoshop shows you this in Image Size (if Resample is disabled), but Photoshop doesn’t know if the image will be resized in another application later, changing the Effective PPI again.

Fortunately, the Info panel in InDesign can show you Effective PPI interactively — see the demo below. And of course Effective PPI is not InDesign-specific. This is how image ppi is calculated for print in any print layout application by any company. Because you can’t get around the math: Final image ppi for print is always the pixel dimensions divided by the physical dimensions times the scale percentage (how much it’s resized) on the layout.

In the demo below, a 3000 × 2400 pixel image is placed into InDesign. Because Photoshop embedded a ppi value of 300 in the image metadata, InDesign reads that, divides the pixel dimensions by the metadata ppi, it works out to 10 inches wide, and the Info panel reports 300 ppi as the Effective PPI. But as you resize the image, InDesign recalculates the ppi based on the new physical dimensions, updating the Effective PPI. That’s how InDesign calculates resolution.

And again, dpi does not enter into this until the job hits the printer. At that time, the printer renders the job at the dpi of the hardware.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Indeed @Conrad_C

Thanks for the video - more or less the same demonstration I have given in screenshots above.

Copy link to clipboard

Copied

Get ready! An upgraded Adobe Community experience is coming in January.

Learn more